COMMUNITY

“When schools form partnerships with families and the community, the children benefit” (Eptein, 2010)

What is this about?

What is this about?

This section of resources will explore the issue of school community links. Partnerships between school staff, families, and community members are vital for ensuring the success and full participation of all students (Epstein, 2011,2012; Haines et al., 2015).

Based on considerable evidence of case studies and project reviews, under the right conditions, and given the right precautions, the greater participation of more actors can help improve the quality of, and the demand for, basic education (Shaeffer, 1994, p.13).

Question for reflection on Community:

- Are parents, teachers and students in your school seen as partners in education?

- How is your level of communications, interactions, and exchanges across these four important contexts: leaders, parents, teachers and students?

- Is there a guide/policy in your school for the creation and maintenance of systematic connections with families and communities?

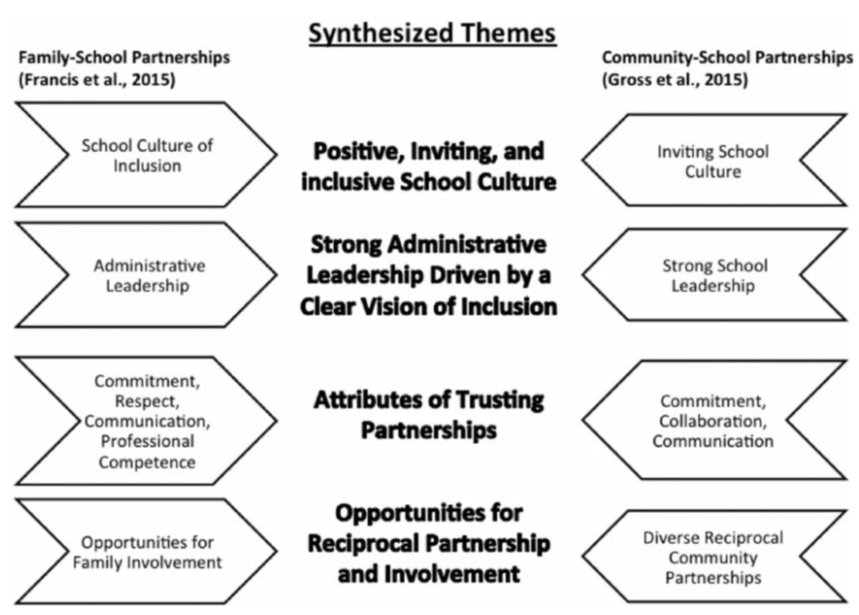

- You can use the two following figures to have a reflection about the situation of your school regarding to the six types of involvement (First figure; Espstein, 2010). The second figure comes from Haines et al (2015) and guides you to have reflection about the four primary themes regarding family–community–school partnerships in inclusive schools:

Espstein, 2010

Haines et al (2015)

Why is this important?

Trusting partnerships among school and community contribute to student success and, ultimately, to creating a democratic community, especially in schools with diverse populations (Tschannen-Moran, 2014). Close connections between schools, families and communities are necessary for several reasons: to minimize the achievement gap,to improve tstudent learning, achievement, behaviour and attendance (Haines et al., 2015) and to contribute to increase the graduation rates for low performing schools (Wolfe, 2008). At the same time, school connectedness has been recognized as a fundamental protective factor relating to student health and development, academic achievement and learning opportunities and involvement in crime (Rowe & Stewart, 2007).

There are many reasons for developing school, family, and community partnerships. They can improve school programmes and school climate, provide family services and support, increase parents’ skills and leadership, connect families with others in the school and in the community, and help teachers with their work. However, the main reason to create such partnerships is to help all youngsters succeed in school and in later life (Epstein, 2010, p. 82).

What does this mean for leadership?

School and school leaders make choices. School leadership is one of five essential supports for successful school transformation (Bryk et al, 2010; Capers & Shah, 2015). School, family, and community partnerships cannot simply produce good results and successful students. Because of that, school leaders have to plan partnership activities to engage, motivate and guide students to achieve success. There are schools that have expanded and sustained community links at the school and systems level where the leadership have played a major role (Capers & Shah, 2015). Leadership, is vital to creating and sustaining partnerships with family and community members (Sanders, 2014; Haines et al., 2015).

Involvement and commitment only come with willing action based on understanding, as defined by step seven of Shaeffer’s (1994) Ladder of Participation. The ladder ascends from the lowest rung where communities simply make use of a service to the seventh rung where communities participate in real decision-making at every stage, ‘This implies the authority to initiate action, a capacity for ‘proactivity’, and the confidence to get going on one’s own’ (Shaeffer, 1994, p.17).

Within a school we can wonder how can practices be effectively designed and implemented to enhance partnership. Reaching real community involvement in the school is a two way relationship (Schaeffer, 1994):

- From the school to the community.

- From the community to the school.

These relationships do not just happen naturally. They need to be planned for and worked on with leadership hasving a clear role. The consensus among researchers, policymakers and practitioners is that ‘leadership makes a difference’ to the quality of learning in schools still being reinforce by evidences ( Robinson et al., 2008).

FitzGerald and Matthew (2016) argue that “the physical locus of learning must shift from academic to family/community spaces if aspiring leaders and their professors are to move beyond learning about engagement to engaging. Locating community engagement in the halls of academia rather than in and with the community teaches college students about engagement, not to engage”. (2016, p. 113). At the same time, they state that (FitzGerald & Matthew, 2016):

- An effective school leader needs to be aware of, locate, and describe his or her own positionality within a system as well as the positionality of others, namely families and community members.

- An effective school leader needs to be able to listen to and dialogue with families and communities.

References

- Bryk, A., P. Sebring, E. Allensworth, S. Luppescu, and J. Easton (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Capers, N. & Shah, S. (2015). The power of Community School. VUE, 40, 27-35.

- Chrispeels, J. (1996). Effective Schools and Home‐School‐Community Partnership Roles: A Framework for Parent Involvementschool Effectiveness and School Improvement: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice, 7 ( 4), 297-323.

- Eptein, J. (2010). School/family/community Partnerships: Caring for the Children We Share: When Schools Form Partnerships with Families and the Community, the Children Benefit. These Guidelines for Building Partnerships Can Make It Happen. Phi Delta Kappa, 92 (3),81-96.

- Epstein, J. (2011). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press

- Epstein, J. (2013). Ready or not? Preparing future educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Teaching Education, 24(2), 115–118.

- FitzGerald, A. M. & Militello, M. (2016).Preparing School Leaders to Work With and in Community. School journal Community, 26 (2), 107-234.

- Haines, S., Gross, J., Blue-Banning, M., Francis, G. & Turnbull, A. (2015). Fostering Family–School and Community–School Partnerships in Inclusive Schools: Using Practice as a Guide. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(3) 227– 239

- Robinson, V., Lloyd, C. & Rowe. K( 2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly 44, (5), 635-674.

- Rowe, F. & Stewart, D. (2007). Promoting school Connectedness through whole school approaches. Health education, 107 (6), 524-542.

- Sanders, M. G. (2014). Principal leadership for school, family, and community partnerships: The role of a systems approach to reform implementation. American Journal of Education, 120, 233-255.

- Shaeffer, S. (1994) Participation for Educational Change, a Synthesis of Experience. Paris: IIEP.

- Sheldon, S. (2003). Linking School–Family–Community Partnerships in Urban Elementary Schools to Student Achievement on State Tests. The Urban Review, 35 (2), 149-165.

- Tschannen-Moran, M. (2014). Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley

- Wolfe, F. (2008). Fundation: School-Community links vital for students. Education dayly, 41 (166),